Dunn Ranch Prairie

Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

Overview

The Central Tallgrass Prairie Eco-region spans 110,000 square miles and six states. In 1999, The Nature Conservancy purchased a 2,287 acre plot located within the Grand River Grasslands (100,000 acres), more than 1,000 acres of which have never been plowed. Today Dunn Ranch Prairie is the anchor site of a 70,000 acre prairie restoration. While the site now teems with recovering wildlife, the most charismatic species it supports is Bison bison, the American Bison, reintroduced at Dunn Ranch in 2011.

The Nature Conservancy requires a holistic landscape systems vision for Dunn ranch - a dynamic, open-ended plan that generates sustainable ecological, economic and social outcomes over the long term. This strategic landscape systems plan involves four main trajectories of analysis:

1. The first is a deep biophysical explication of the Grand River bioregion that links regional biology, watersheds and water systems, prairie plant systems, and large-scale geological continua with short and medium term climatic trends, all of which impact the flora and fauna gradients that shift and change as the planet warms.

2. The second is a multi-scale economic analysis that locates Dunn Ranch as a commercial entity within macro and micro economic trends to do with bison farming, cattle-rearing, nature/ecotourism, educational opportunities, scientific endeavors, local community agricultural practices, and global trends that influence these. A typical question within this investigative theme would be: How can conservation interface with production agriculture in ways that meet the needs of both?

3. The third component of the landscape systems strategy involves a socio-cultural analysis that examines the deep human histories of the region. Stewardship of the tallgrass prairies requires an understanding of past management practices (including the traditional ecological knowledges of indigenous inhabitants) and a sense of how and why specific management practices have evolved. This analysis, while necessarily historical, also engages a synchronic continuum of current community value systems and lifestyle practices (including animal husbandry and hunting) as these impact on bioregional ecosystems. For instance, Dunn Ranch’s neighboring farmers are largely a community of cattle-ranchers belonging to the local cattlemen’s association. How can The Nature Conservancy promote sustainable ranching that supports healthy watersheds, diverse grasslands and their associated wildlife?

4. The fourth component of the landscape systems plan focuses on the development of a new field station at Dunn Ranch. The TNC facility has become an innovative technology and research center, conducting dozens of studies on grassland species, plant communities, prairie assemblages, ecological performance, and pollinator health. Since bison were introduced the facility has connected with bison research initiatives around the globe, and developed bison technologies and management practices appropriate for contemporary herd care.The new field station would incorporate science labs, accommodation, seed-raising units, tourism and hunting facilities. The location, water-management systems, and overall environmental responsiveness of the new facility will be generated from the landscape analyses, from discussions with scientists and TNC associates, and studies of other organizations that have developed similar field stations.

Temperate grasslands are the least-protected major habitat type on earth. Dunn Ranch, 3,200 acres of temperate grasslands, offers the last chance to conserve a living landscape of tallgrass prairie on deep soil. The Nature Conservancy and the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts are building a partnership to ensure that the Dunn Ranch community of conservationists, researchers, and wildlife managers have the strategic and physical resources they require to achieve their mission.

To be continued...

Landscapes of Power

Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

OVERVIEW

power (n) 1. a source or means of supplying energy 2. the ability to act or produce an effect 3. possession of control, authority, or influence over others 4. legal or official authority, capacity, or right (v) 1. to supply a device with mechanical or electrical energy 2. to move or travel with great speed or force 3. to inspire, spur, sustain

energy (n) 1. power derived from the utilization of physical or chemical resources 2. a source of usable power 2. the capacity of a physical system to perform work

In December, at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (the 21st Conference of the Parties AKA COP 21), 195 countries agreed and signed a global agreement pledging to accelerate a global shift to clean energy by reducing carbon pollution, assessing and bolstering commitments every five years, protecting those most effected by climate impacts, and assisting developing nations to expand clean energy economies. It calls for holding temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, which is largely regarded as the tipping point for catastrophic impacts. The Paris Agreement is the most recent measure to attempt to address climate change. Previous agreements include the Montreal Protocol (original signed in 1987, went into effect in 1989) and the Kyoto Protocol (signed in 1997, went into effect in 2005) which have had limited success.

The Paris Agreement is largely being hailed as a new approach and conceptual breakthrough to addressing climate change on a global scale. Instead of delimiting a list of conditions that every nation must meet, it sets up the framework for each country to establish commitments and transparency to review the progress toward these. In essence, the treaty provides the means to aggregate, measure and access each country’s contributions, relying on peer pressure and competition rather than unenforceable targets.

This studio focuses on energy production and power as a key factor in attaining the goal of this global shift toward zero carbon pollution. Energy is spatial. But it is also cultural, social, and political. What does this transformation mean for the landscape? What are the social and cultural implications? What is the role of landscape architecture?

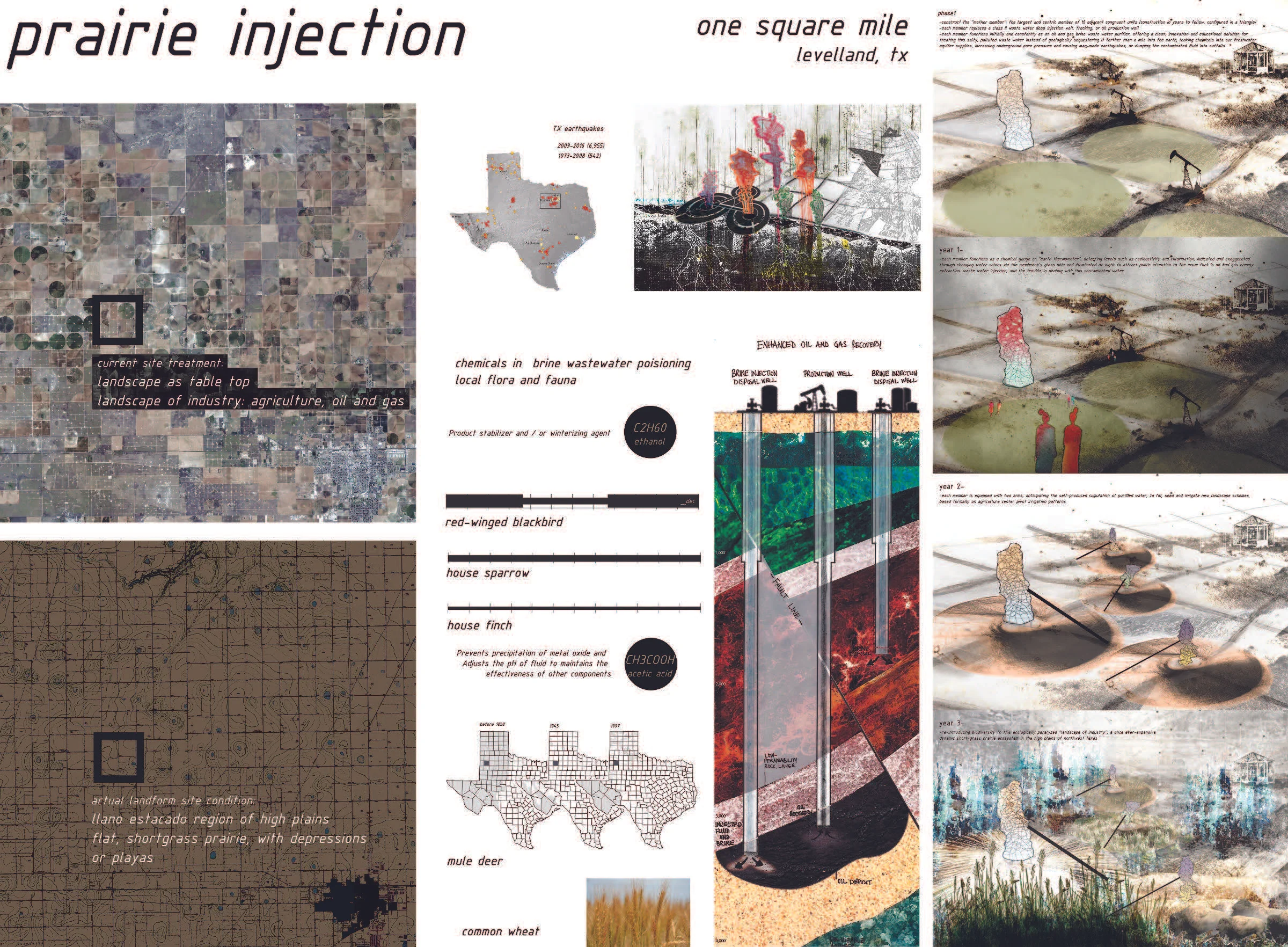

Project 2 Applied Research asks students to explore and reveal the physical implications and consequences of energy extraction through a series of drawings that connect energy to device to landscape. The students began by describing a current device through architectural drawing (section, plan, perspective) including the interface with the landscape and interaction with energy source. Using this drawing as a starting point, students invented a new, fantastical device to illuminate our energy dilemma typically hidden to the casual observer. These devices aim to suggest solutions through imaginative and possibly satirical proposals. The inventions were modeled and then drawn.

Prospective Exhibition on Landscapes of Power

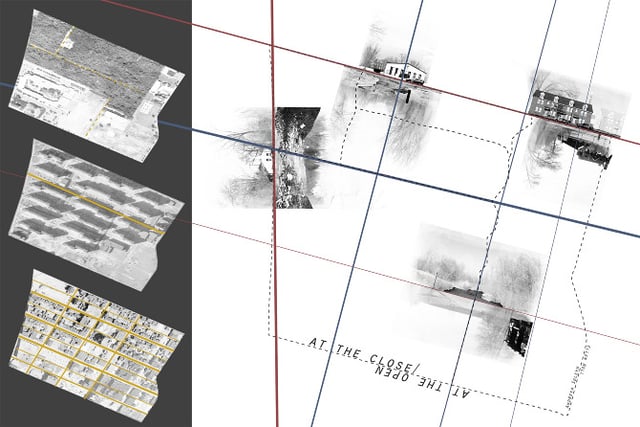

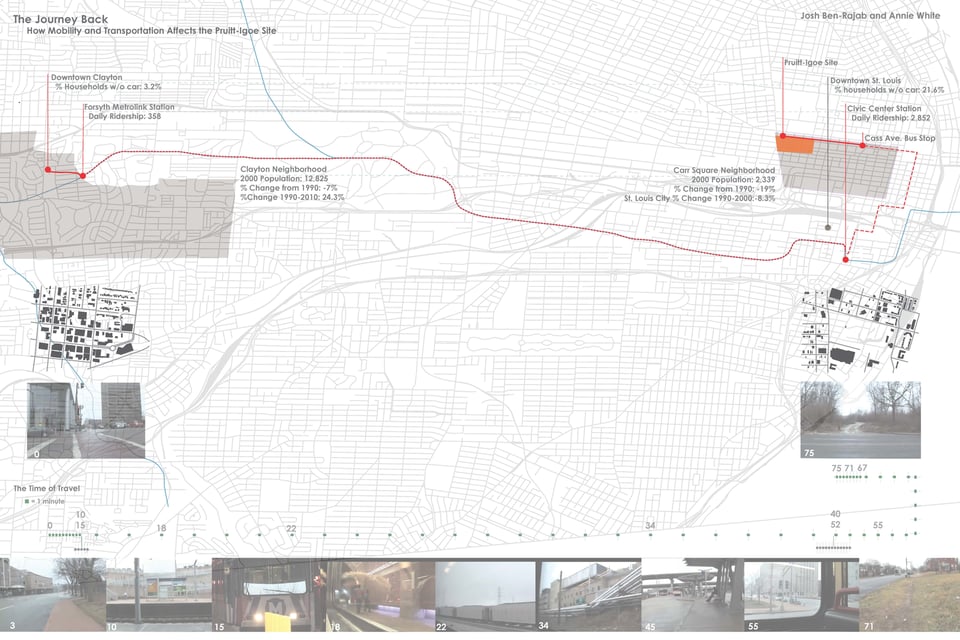

The Machine in the Ghost [Pruitt Igoe]

Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

Overview

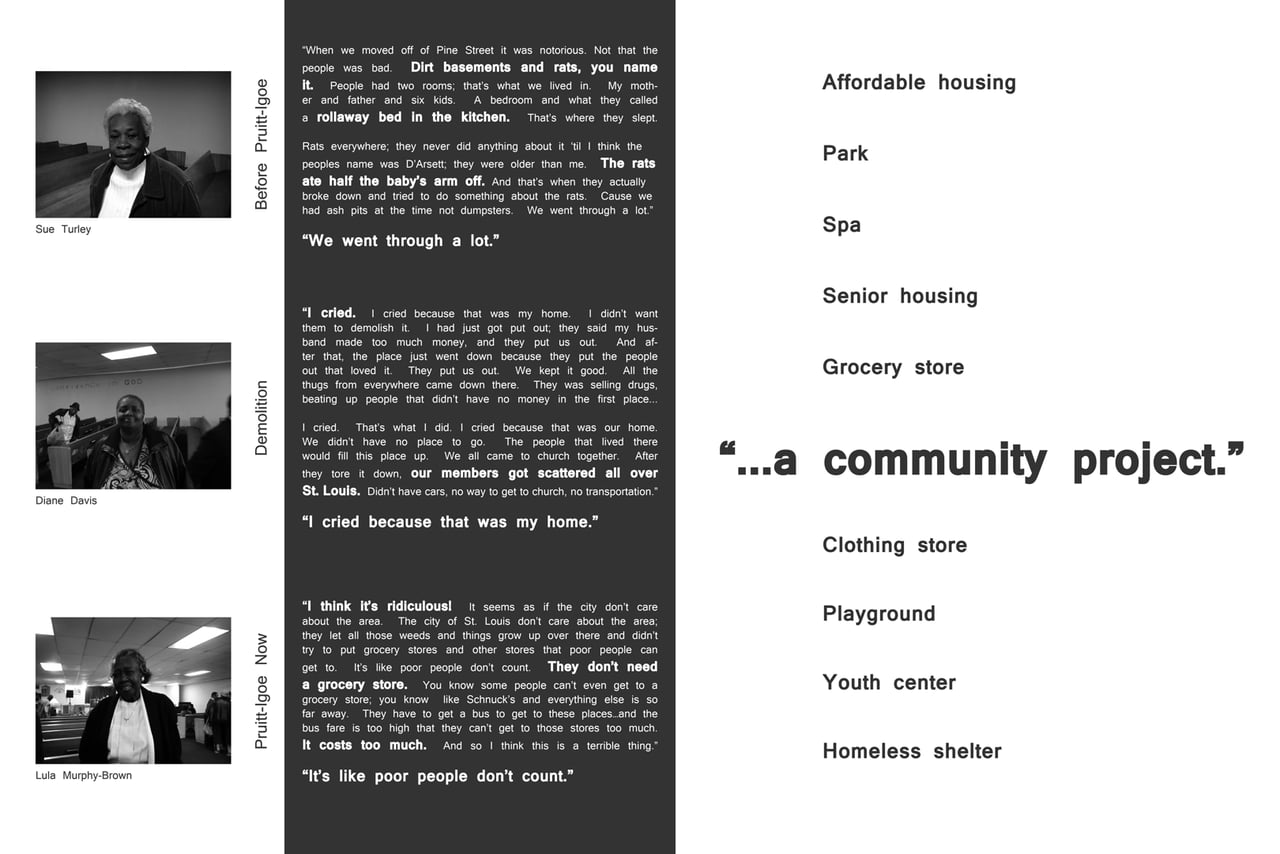

At the edge of downtown St. Louis, there is a 57 acre tract of land bounded by Cass Avenue, 20th Street, Jefferson Avenue and Carr Street. It has been described as an urban forest, a mess, beautiful, dangerous, serene, a disaster, rare, cursed, a tragedy and stunning. Some deem it “abandoned” or “vacant”; others - a “sanctuary”.

Ten thousand years ago, this area was likely part of a spruce-fir forest. After that, grassland and prairie. Before the expansion of the city, cropland. As the city expanded, it became the Desoto-Carr Neighborhood. In the 1950s it was redeveloped into the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project. Just 20 years later the project was demolished. Now, almost 40 years later, most still refer to this area as (the former) Pruitt-Igoe even though it barely resembles that past.

This area in north St. Louis is the subject of this landscape architecture studio. Through design research, discussion and development, students will develop a critical positions surrounding issues of “ecological restoration”, the role of history in design development, intervention in the landscape, and even the role of the landscape architect. We will begin the semester by visiting the site to develop our own impressions and understanding. We will meet with a historian to learn the recent past. Students will consider how this site is connected to larger systems and related to other areas in St. Louis (and perhaps elsewhere).

This studio will focus on techniques (both traditional and inventive) to read, record and interpret a site in order to develop methodologies that reveal the hidden and evanescent. The beginning of the semester will focus on reading and recording, inventing and interpreting. The later part will focus on redefining, redistributing and possibly reconfiguring. Students will explore methods of sensing, recording, interpreting, translating and visualizing environment data. After initial research, students will develop a strategy to record, interpret and translate environment data for the purpose of analyzing relationships. Students will test their ideas through prototypes, models, drawings and documentation, and later, make proposals that range in spatial and temporal scales.

Catalyst: Minneapolis, Memphis, St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

Catalyst / Studio North | South

Overview

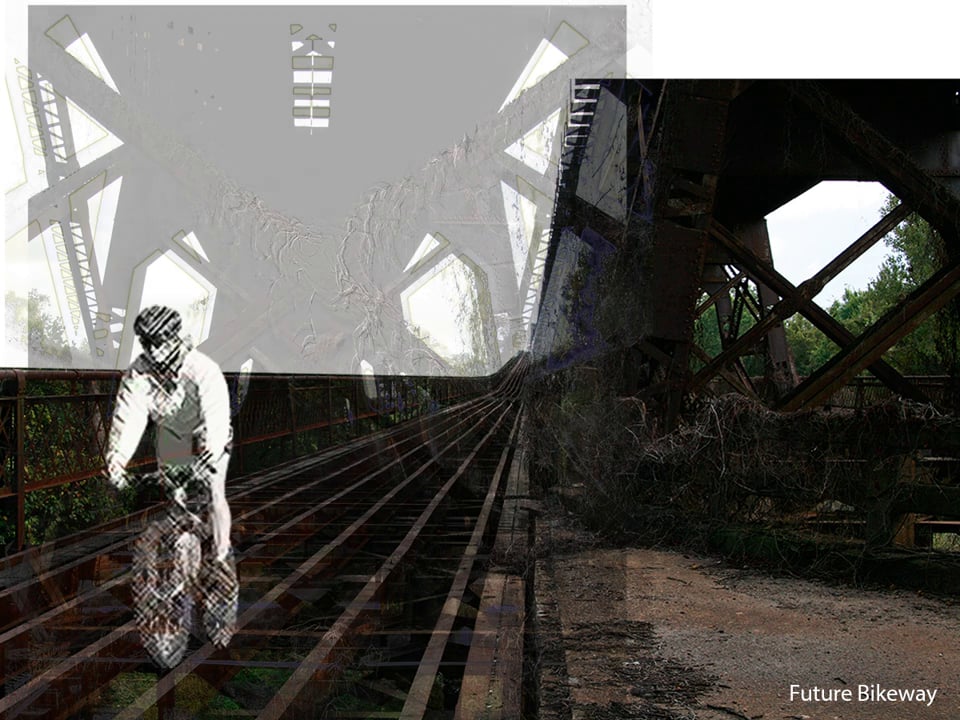

The Mississippi River supplies water to people, farms and industries; it provides transportation for goods and services. It plays a major role in the health, culture and prosperity of the 31 states it touches. Catalyst builds from the North | South studio conducted last fall which looked at sites in both Minneapolis, Minnesota and Memphis, Tennessee. Using the previous semester work as a springboard, the studio will focus on selected sites along the riverfront that offer opportunity for public interaction (recreation, education, economy, etc.) as well as potential ecological impact for the river system as a whole.

This studio is a comprehensive studio for graduate students in the landscape architecture program as well as an option studio for architecture/urban design students. Students will be asked to confront multiple scales and time frames, identify opportunities of policy and partnerships, and develop innovative proposals for resiliency and sustainability. The studio focuses on mediating between ecological and urban systems, incorporating ephemeral, cyclic and adaptable tactics for design and management.

Students will research and select a site based on initial analysis, identified objectives, project potentials and individual interest. With instructor assistance, students will be responsible for defining the scope of their project and developing appropriate design responses. Emphasis throughout the studio will be placed on articulating an understanding of site character, understanding diversity of potential users and experiences, refining project(s) at multiple scales, and consideration of design over time. Students will propose ecological, hydrological, and/or architectural interventions at multiple spatial and temporal scales. Students can expect to travel during the designated travel week to visit sites, potential partners and significant cultural features in multiple cities (Minneapolis, St. Louis, Memphis) that will inform the design process.

Pruitt Igoe: Pasts + Futures

Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

Overview

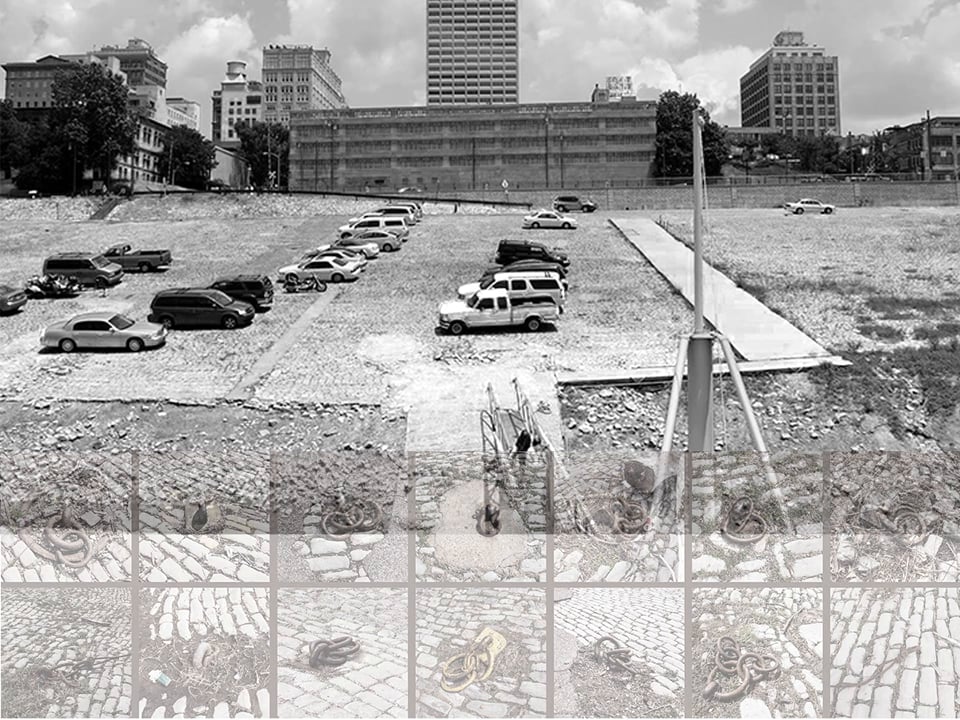

The studio will reach across scales and time to map histories and design futures for the long-time vacant site where the Pruitt Igoe housing project once stood at the edge of downtown St. Louis City. Pruitt Igoe represents a space of particularly loaded urban, environmental and social histories in St. Louis. It is the site where an enormous, multi-building public housing experiment played out in the 1950’s, as part of a Modernist vision to restore health in the city through ‘urban renewal’. After becoming an unlivable scene of crime and neglect, it was demolished some 20 years later and has stood vacant ever since. Today it is a wild, vegetated landscape very close to the heart of the downtown, and the center of new development visions for St. Louis. Students will be asked to grapple with the legacy and realities of this place where contested agendas, memories, meanings, facts, and natural and material systems interact and overlay. In doing so, students will be asked to challenge terms like “sustainability,” “urban development,” the “public” and “landscape” in the city.

The studio runs concurrent with an open ideas competition Pruitt Igoe Now. Students will draw from materials provided by the competition website including viewing the recent documentary The Pruitt Igoe Myth, while also conducting original research from across other sources (in groups). After the substantial research and mapping/analysis phase, students will build broad-based proposals for the Pruitt Igoe site. Students will submit their design proposals for entry to the competition, then will work to develop schemes further in the remaining portion of the semester.

Cities comprise layered and complex territories, where public and private realms operate both regionally and locally. The studio is organized in a way that will guide students in how to first ‘see’, then engage, sites in relationship to these broader systems. Systems include environmental systems like water management and brownfield considerations; economic systems like tax incentives and real estate development variables; social systems and the associated layers of urban histories in St. Louis; spatial, material, organizational and circulatory systems which inform typologies of the city and other patterns of urbanization. Students will use their acquired understanding of landscape/urbanism systems to formulate varied design proposals that also engage time and scale in re-imagining the site as an intrinsic part of a dynamic city.

Combined Architecture / Landscape Architecture Core I

Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri

OVerview

In psychology, heuristics are simple, efficient rules, hard-coded by evolutionary processes or learned, which have been proposed to explain how people make decisions, come to judgments, and solve problems, typically when facing complex problems or incomplete information. These rules work well under most circumstances, but in certain cases lead to systematic cognitive biases. Complexity has always been a part of our environment, and therefore many scientific fields have dealt with complex systems and phenomena. Indeed, some would say that only what is somehow complex – what displays variation without being random – is worthy of interest. The use of the term complex is often confused with the term complicated. In today’s systems, this is the difference between a myriad of connecting “stovepipes” and effective “integrated” solutions. This means that complex is the opposite of independent, while complicated is the opposite of simple. While this has led some fields to come up with specific definitions of complexity, there is a more recent movement to regroup observations from different fields to study complexity in itself, whether it appears in anthills, human brains, or stock markets.

The first semester graduate design core studio of architecture and landscape architecture explores foundation design principles, comprehensive skill sets, and critical thinking. Rigorous methodologies and inquiries will be developed to appreciate the heuristics in developing the process of design. Design helps organize social life via the articulation/perception and the conception/comprehension of spatial order. The studio will concentrate on the individual development of the design process through the production of complex design projects. Students are asked to engage the subject matter presented through active learning, which requires exploration, experimentation, and questioning through an iterative process. The experimental processes will focus on the procedures of organizing space and form through site and structure manipulations. Articulating the relationship between space and form in current contemporary culture will allow each student to develop a strong sense of craft and a critical and theoretical relationship to the built environment. In this pivotal semester the students are asked to commit to design and the importance of understanding the speculative nature of spatial order. Issues of sustainability will run through the semester starting from your personal space and evolving to the specifics of your project site.